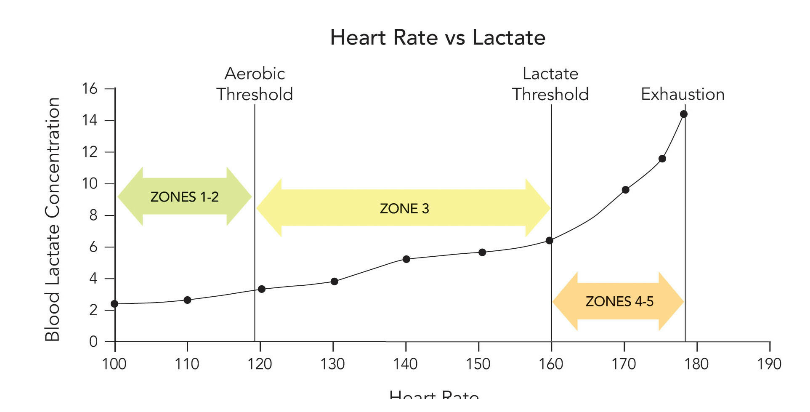

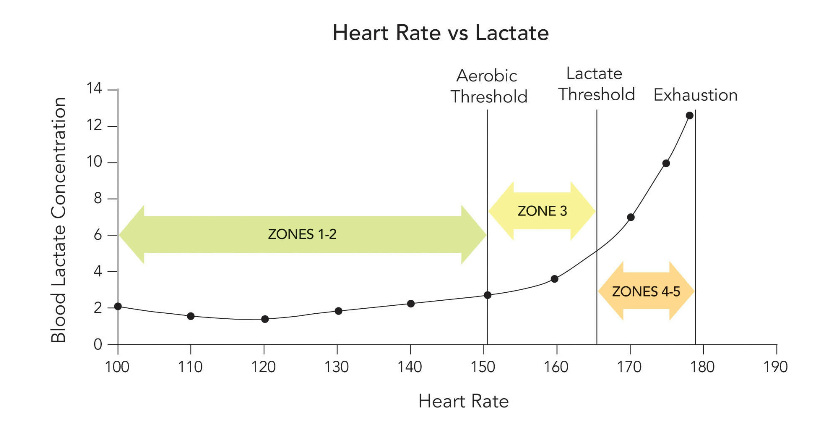

This is the endurance training book that helped everything to click into place for me. Everyone stresses the importance of building a strong aerobic base, but the authors here actually explain why: your aerobic energy system uses lactate as a fuel, so the more developed your aerobic system the more lactate you can clear a higher energy outputs, meaning you can push harder for longer.

What we are doing is creating a model, an artificial delineation and segregation of these systems that are, in reality, intimately interconnected and interdependent. This simplified model format is commonly used in science to allow complex systems and ideas to be broken into their constituents, which may then be better understood. The art of coaching comes, in part, from an understanding of the interconnectedness and interdependence of these systems.

Effective endurance training works by causing fatigue to the systems described above. This in turn induces adaptations to occur with these systems. Because these systems are interconnected, monodirectional training (e.g., training primarily one system) will, after some time, inevitably yield diminishing returns. An athlete experiences this as a plateau, and in the worst cases, a degradation, in performance.

Think of metabolism as a miniature ATP recycling plant in the muscle cells. After ATP is broken apart to extract the energy needed for muscle contraction, then the metabolic recycling plant using the energy from food reassembles the ATP molecules so the whole process can keep going.

It’s a good thing we recycle ATP because it is a heavy molecule. The amount of ATP required to sustain a resting metabolic rate for one day would amount to about 60–70 kilograms. Basically an extra “you” if we had to store and carry all this ATP.

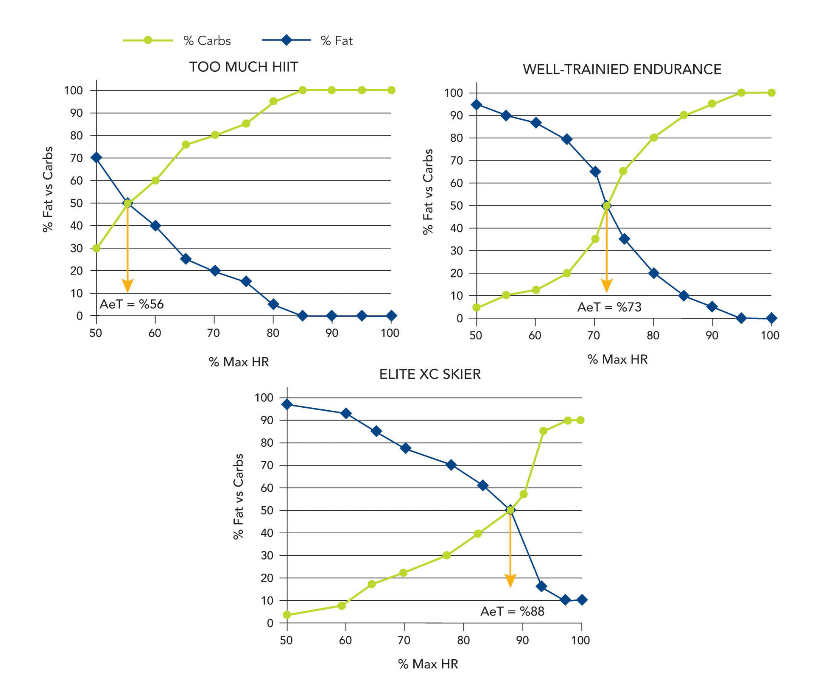

Those with a history of high-volume, low- to moderate-intensity training will have slow twitch muscles that are aerobically well adapted and be able to sustain higher speeds aerobically. Likewise, those with a history of higher intensity will have predisposed their metabolism toward the anaerobic/carbohydrates use.

The subject of lactate measurements can, and does, fill a book (The Science of Winning by Jan Olbrecht).

Summary of Metabolism as It Relates to Endurance

Before moving on to the implications of what you’ve just read, let’s take a moment to restate what we know so far:

From a performance standpoint, the metabolic fate of that pyruvate molecule is the essential event in determining endurance in events longer than two minutes. Physiologically speaking—the end goal of most endurance training should be to encourage that pyruvate molecule to enter the mitochondria and undergo aerobic metabolism.

Lactic acid gets the bad rap, but it’s worth remembering that lactic acid only forms when pyruvate hangs around and does not enter the aerobic metabolism.

There are two ways we can raise the Lactate Threshold:

Each of these requires different and to some extent mutually exclusive forms of training.

Athletes who overuse high-intensity training methods will usually have a low AeT because their aerobic metabolism has become detrained while the anaerobic metabolic pathway has become very powerful. We call this condition Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome (ADS). It is reflected in a slow (often shockingly slow) AeT pace. These athletes will be dismayed that despite all their hard training, they still can barely get above a jog or even a walk before exceeding their AeT. These athletes typically respond with disbelief: How can they possibly be getting any training benefit from such a slow (perhaps even walking) pace? This low aerobic capacity has only one cure: a high volume of low- to moderate-intensity training.

One of the strongest training stimuli for increasing the aerobic recycling rate of ATP is glycogen depletion in the ST muscles. This is best done with long-duration, low- to moderate-intensity training sessions because it takes long durations to deplete the glycogen of these already well-endurance-adapted ST muscle fibers.

The lesson is that, if you suffer from ADS, then the AeT pace is going to be very slow and very far from race pace. Accept that this is all the power your aerobic system is capable of in its current deficient state. No ifs, ands, or buts about it. Faking it by running at a faster pace to soothe your ego will only slow the development of that aerobic engine.

Given the above discussion, the best method for improving endurance is to do these two things:

Achieving this is tricky because doing the first requires one type of training while doing the second requires a very different kind. Increasing aerobic capacity requires a high volume of low-to-moderate-intensity work. Improving the lactate shuttle, on the other hand, requires high-intensity training that produces significant levels of lactate.

The history of endurance training is the story of trial and error over hundreds of years by thousands of coaches and millions of athletes. While the evidence is anecdotal, the population size is so big that coaches can weed out what does and doesn’t work. New stuff is tried all the time. Good ideas stay, bad ones get rejected or modified until they are good ideas. These ideas must stand the toughest test of all, the stopwatch, in the highest levels of competition.

Fat stores, even in a lean, well-trained athlete, are virtually limitless (up to 100,000 calories of intramuscular fat). On the other hand, glycogen stores will rarely reach 2,000 calories even in the well trained.

A strong training stimulus that is ideal for causing desirable adaptations to the aerobic system will have a negative effect on the anaerobic system. Any workout that has a powerful anaerobic training effect will diminish the aerobic system’s capacity to do work.

We can bias our metabolism toward the maximum anaerobic endurance required by events ranging from one to two minutes in length, or we can bias our metabolism toward events that last many hours and even days. But we can never optimize it to both at the same time. While this is an amazing range of potential specialization, the real lesson is that we have to target the training we do to get the outcome we desire.

We follow an approach to training for endurance that has stood the test of time in all of the conventional endurance sports for more than sixty years. The following is a distillation of this successful approach: You will never maximize your endurance potential without first maximizing your basic aerobic capacity (AeT).

Despite the prodigious amount of scientific research examining the myriad qualities that comprise endurance, it is the coaches and not the scientists who have been at the forefront of establishing the most effective training methods. Through a trial-and-error approach, the coaches of the past have discovered what did and what didn’t work. Failed training methods were discarded or modified until the most effective methods rose to the top in an evolution-like process. The scientists come along later to shed light on why those successful coaching methods work, and that in turn supports the intellectual framework.

Bob Bowman, most famous as Michael Phelps’ coach for his entire phenomenal career, has used the terms Capacity Training and Utilization Training to describe two different types of training that swimmers can use. Here is how Bowman defines these terms:

Those just starting aerobic training and/or those with Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome can do almost all their aerobic base training in Zone 2 (foregoing Zone 1 completely) because their pace at this intensity is going to be slow enough that their muscles will not get too much of a beating. However, those athletes with a high AeT and whose pace at this threshold is fast will not be able to do much Zone 2 training in a week without risking overtraining. They will need to do much more of their aerobic base work in Zone 1 and even the Recovery Zone.

Zone 3 training is most effective when the athlete has sufficient basic aerobic capacity; when the vacuum cleaner is big and powerful. How much capacity is sufficient? When you’ve raised your AeT to be within 10 percent (elite athletes can have a Z3 spread of 6–7 percent or only 10 beats) of your LT as measured by either heart rate or pace. With more than a 10 percent spread between thresholds, an athlete still has aerobic deficiency and needs to build more aerobic base. Those who have less than a 10 percent spread between thresholds will need to reduce or even drop Z2 training, substituting Z3 workouts.

If you miss a week of training due to work, travel, or sickness, you can’t pretend that you actually did all that training and progress to the next part of the plan. Your body will not be prepared for the next step, and you’ll likely have setbacks. How you manage this discontinuity depends on its length and the reason for it. Occasional breaks of a day or two are not much of a problem as long as they do not diminish the training load by more than roughly 5 percent in a month. Frequent or prolonged breaks from training that amount to more than 5 percent of the monthly volume do create a need to adjust your subsequent training by taking a step back in the plan.

As a general rule, beginners (under 350–400 hours each year) can increase training load, as measured by time, by as much as 25 percent per year.

People with years of endurance training, especially in childhood through adolescence, will have retained many of the structural adaptations made during those years even if they have been relatively inactive recently. Adaptations to training come much slower after the teens and twenties and will require much more work to make happen after middle age.

High-intensity exercise and strength training require the longest recovery times of two to three full days before you’ll be prepared to absorb a similar load. Low-intensity endurance workouts of two to three hours or less will normally be recovered from in eight to twenty-four hours. Long-duration (over two hours) training at even low intensity may require twenty-four to forty-eight hours for the restoration of glycogen stores.

Eating during and within thirty to sixty minutes of finishing these long workouts will greatly reduce the time needed for recovery, sometimes by days.

If you do not feel a progressive increase in energy, strength, and overall fitness from week to week, you are either training too hard, not allowing enough time for recovery, or your active recovery sessions are too intense.

For athletes who are pushing the limits of training that their bodies can absorb, recovery strategies become an integral part of the overall plan. For those who are time limited rather than energy limited in the amount of training they can fit in during a given week, recovery can still be a useful tool, but may not be so essential.

Consume 100–200 calories in the first thirty minutes post exercise of over an hour. Have these calories in a form that does not upset your stomach (you may need to experiment). Eat these in a ratio of 3:1 or 4:1 of carbohydrates to protein. It is during this post-exercise window that the muscles can replenish their glycogen stores quickly. Miss this window and recovery can be delayed by up to days depending on the workout/race.

If you have the chance to anticipate an upcoming break in your schedule, it is possible to boost the training load for a short period, say a week, going into the business trip or family visit that’s disrupting your training. Then, use that planned break as a recovery period, trying to get in just a few short, easy workouts.

I have spent years consciously reframing normally bad situations into positive ones, an alternative response protocol that has enabled me to finish many of the toughest ultramarathon and mountain objectives. More importantly, however, it has positively influenced my perspective on nonrunning aspects of life as well. When confronted with dramatic or stressful life events, I find I am able to remain calm and measured. In every challenge there is something to be learned and a way to be a better person for it. In athletics as well as in life, find the silver lining and keep moving forward.

Determining your AeT establishes the most critical metabolic reference point you can know and serves as the foundation from which to build your training plan. We recommend that you know this intensity.

In hundreds of field tests in moderate-to-well-trained endurance athletes, we have seen a good correlation between the heart rate that can be maintained while breathing only through the nose or while carrying on a conversation with the blood lactate level of 2mMol/L (the commonly accepted measure of AeT). The caveat here is that this works only for those with good aerobic training backgrounds. For those who have no history of aerobic endurance training, or those who have a training background heavily biased toward high-intensity, short-duration work, or people with no history of regular exercise, these ventilation markers fail to correlate with blood lactates.

When it comes to basic aerobic training (Zones 1 and 2): If you can’t do the same workout you did yesterday again today, and tomorrow and the day after for days on end, then you are doing too much. You are doing too much volume or too much intensity for your current regimen to be considered an aerobic base-building program.

While an elite runner is not running slowly when he is in his low-intensity zones, the sad reality is that for many athletes, their Zones 1–2 training will be an excruciatingly slow pace that seems like it cannot possibly have any beneficial training effect at all. If you find yourself in this situation, welcome to the club: the Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome (ADS) Club. The reason your AeT pace is so slow is that your aerobic capacity is low. In other words, your aerobic metabolism can crank out only enough ATP to support what may be a disappointingly slow pace. The only way to increase your speed at an aerobic level of intensity is to increase your aerobic capacity, which means you must train at and below your AeT.

Do not feel that if you are not running right at your aerobic limit, you are not getting the aerobic benefits.

Threshold Intervals (Zone 3): The purpose of doing these intervals is to raise the LT speed and to increase the duration that it can be maintained.

Aerobic Power Intervals (Zone 4): Aerobic power (often called VO2 max) intervals are conducted at intensities greater than LT; usually at near 95 percent of max heart rate. Total volume of the workouts can range from fifteen to thirty minutes. These workouts maximally utilize the capacities of all the systems involved in endurance. The effectiveness of these workouts is very reliant on the athlete’s muscular endurance. If your leg muscles become tired and you are forced to slow down, causing the heart rate to fall below the Zone 4 range, you are no longer getting the intended benefits of Zone 4.

Blind adherence to any training plan is an almost surefire route to inferior results, if not disaster.

The best rule of thumb for those new to structured training is: If you are not seeing small improvements over the course of several weeks and you are using the principles presented in this book and training more than eight hours a week, then something is amiss. You may not be recovering well due to extraneous stressors in your life or the training workload is too high or the progression is too fast. You need to make adjustments to either your training load or your lifestyle, or both.

We want to once again emphasize the principles that you need to follow: maintaining consistency in your training routine while gradually increasing the training load and modulating the training from hard to easy over days and weeks.

Aerobic base workouts: Start your planning by selecting one day each week for your long workout. Aim for between 30–40 percent of your overall weekly distance/vertical on this one run/ski.

Guidelines for progressing the training load:

I'm James—an engineer based in New Zealand—and I have a crippling addiction to new ideas. If you're an enabler, send me a book recommendation through one of the channels below.