I was keen to know more about the context surrounding the signing of the Treaty, and the primary points of contention. This book is a thorough and well-balanced introduction which does a good job of explaining the situation without demonising either party. The second half of the book was pretty dry, so I ended up skimming through it, but the first half was solid.

The northern chiefs Hongi Hika and his ally Waikato travelled to England in 1820 with the missionary Thomas Kendall. The Church Missionary Society, Kendall’s employer, hosted the visit and possibly commissioned this portrait. Kendall had begun putting te reo Māori into written form, and helped Hongi learn to write. Hongi and Waikato spent two months at Cambridge University where they worked with the scholar-linguist Samuel Lee on an agreed form for written Māori. In London, the rangatira visited sites such as the Tower, the Armoury and the zoo. But it was their audience with King George IV, monarch of the world’s most powerful nation, that made the rangatira feel they had a special relationship with the British Crown. The men exchanged gifts, with Hongi receiving a coat of chain mail. The visit created a bond that would last.

When each had signed [the Treaty], Hobson shook his hand, saying ‘He iwi tahi tātou.’ According to Colenso this meant ‘We are [now] one people’, but Felton Mathew thought it meant ‘We are brethren and countrymen.’

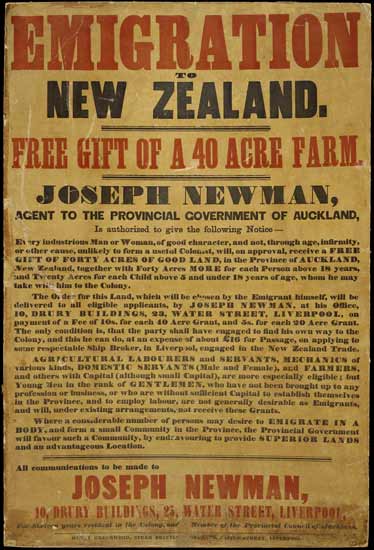

From 1840, Māori gradually became aware that they were no longer free to dispose of their lands as they chose. Under the terms of the Treaty, they could sell land only to the government. If they wanted to sell land and the government did not want to buy it, the land could not be sold to anyone else. If the government agreed to buy the land, officials could set a low price, and then on-sell the land to settlers at a much higher price.

The opponents of the Treaty (of whom there were many, in both New Zealand and Britain) argued throughout the 1840s that the agreement did not in fact guarantee Māori ownership of all land in New Zealand, especially land Māori were not currently occupying or cultivating. In 1844, a British parliamentary committee recommended that any ‘unused’ land should become the property of the Crown. At first the British government vehemently rejected this proposal, but it was included in dispatches to Governor Grey in 1846. Grey shelved the idea as too dangerous, and argued that it was also unnecessary because Māori could be ‘persuaded’ to sell ‘unused’ land at a very low price. He then proceeded to buy the Wairarapa and most of the South Island, encouraging sales with promises of schools, hospitals, special reserves and other benefits. The promises were mostly unfulfilled.

Taranaki settler J. C. Richmond (1822–98) spoke for some (though not all) when he looked forward to the Treaty being overruled so that Māori claims to the extensive bushlands would no longer be able to ‘damp the ardour and cramp the energies of the industrious white man’. Richmond was Native Minister during the period 1868–71.

By the 1870s, it was clear to many Māori that the Treaty offered very limited protection. The 1840 agreement had no power, for example, against the Public Works Acts of 1864 and 1876, which allowed land to be taken compulsorily for public development; nor was it helpful against subsequent legislation such as the Highway Boards Acts, the Railways Acts and a series of Drainage Acts. Officials were not blind to the effects on Māori; indeed, at times they openly acknowledged that the Crown was more likely to take Māori land for public works because it was easier to avoid paying compensation.

Like others, Tuhaere was puzzled by the erosion of fishing rights: ‘They have been taken away, in spite of the words of this Treaty. I do not know how they went. They are not like lands or forests. You have to make an agreement before they can be handed over or taken’

Most speakers [at the first Ōrākei meeting] favoured adherence to the Treaty, partly because of allegiance given in 1840, and partly because of the real advantages they believed they had received as a people, especially the gifts of peace and protection. The British governance introduced by the Treaty had shielded them, they said, not only from foreign invasion but also from intertribal warfare.

I'm James—an engineer based in New Zealand—and I have a crippling addiction to new ideas. If you're an enabler, send me a book recommendation through one of the channels below.