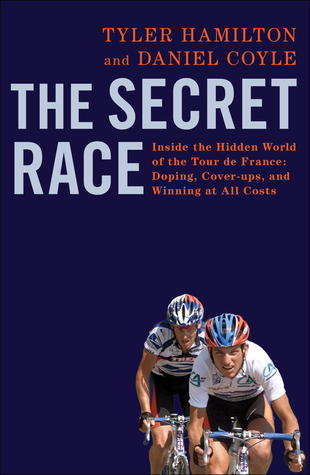

I'm falling further down the cycling rabbit hole. This is the inside story of how doping worked in the Lance Armstrong era of professional cycling, written by one of his close friends and teammates. The logistics involved were incredible; at times taking place in plain sight, with hooded couriers on Vespas being overlooked by fans and media as they all wrestled to catch a glimpse of Lance. The details of the doping itself were also super interesting, and the authors descriptions of what it's like riding in the tour were great.

This moment is why I fell in love with bike racing, and why I still love it—the mysterious surprises that can happen when you give everything you’ve got. You push yourself to the absolute limit—when your muscles are screaming, when your heart is going to explode, when you can feel the lactic acid seeping into your face and hands—and then you nudge yourself a little bit further, and then a little further still, and then, things happen. Sometimes you blow up; other times you hit that limit and can’t get past it. But sometimes you get past it, and you get into a place where the pain increases so much that you disappear completely.

One of our first serious conversations had to do with my blood. Pedro explained that hematocrit was the percentage of blood that contains red blood cells. He explained a new UCI rule that required any rider whose hematocrit exceeded 50 percent—a probable sign of EPO use—to sit out fifteen days. Because there was as yet no EPO test, exceeding 50 percent was not considered doping; instead, UCI president Hein Verbruggen called it a health issue, terming the suspension “a hematocrit holiday.”

It was around this time that I started hearing the phrase “riding paniagua.” (pronounced PAN=ee=ah=gwa). Sometimes it was delivered in a slightly depressed tone, as if the speaker were talking about riding a particularly slow and stubborn donkey. I might’ve finished higher, but I was riding paniagua. Other times, it was mentioned as a point of pride. I finished in the first group of thirty and I was paniagua. I came to discover that it was really pan y agua—“bread and water.” From that, I made the obvious conclusion: riding without chemical assistance in the pro peloton was so rare that it was worth pointing out.

We drew straws for rooms; Scott, being the tallest, naturally drew the straw for the smallest room (when he lay in bed, his head and feet could almost touch the opposing walls).

EPO and other drugs don’t level the physiological playing field; they just shift it to new areas and distort it. As Dr. Michael Ashenden puts it, “The winner in a doped race is not the one who trained the hardest, but the one who trained the hardest and whose physiology responded best to the drugs.”

Eki used to keep track of exactly how many kilometers he rode each year; sometimes we’d ask him the number just to hear it. Usually it was around 40,000 kilometers, enough to circle the earth.

Julien had one rule: No shitting in the camper. He was very clear on this rule. We could tell because every time we saw him, he would point his big finger at us and say, “No shitting in the campa!” in a husky voice. We informed Julien that shitting in the camper was likely to improve it.

We got into a habit of putting our used syringes in an empty Coke can. The syringes fit neatly through the opening—plonk, plonk, plonk—you could hear the needles rattle. And we treated that Coke can with respect. It was the Radioactive Coke Can, the one that could end our Tour, ruin the team and our careers, maybe land us in a French jail. Once the syringes were inside, we’d crush it, dent it, make it look like trash. Then del Moral would tuck the Coke can at the bottom of his backpack, put on aviator sunglasses, open that flimsy camper door, and walk into the crowds of fans, journalists, Tour officials, even police, who were packed around the bus. They were all watching for Lance. Nobody saw the anonymous guy with the backpack, who walked quietly through them, invisible.

Lance was watching too. He tended to treat us like we were extensions of his body, especially when it came to eating. Guys on the team still told the story about the time a couple of years earlier in Belgium when Lance had indulged himself by eating a piece of chocolate cake during a training camp. It must’ve been pretty good cake, because then Lance ate another piece. Then, unthinkably, he ate a third. The other Postal riders watched him eat with a sinking feeling: they knew what was going to happen. The next day in training was supposed to be an easy day. But the cake changed that. Instead, Lance had the team do a brutal five-hour ride, to burn off the cake only he had eaten. When he sinned, the whole team had to pay the price.

Cecco swiftly diagnosed my main shortcoming: I lacked top-end speed. Under Postal, my engine had been trained over the years to be a diesel, capable of producing long, steady power. What won big races, however, was not diesels but turbos, riders capable of producing five minutes of high-end power on the steepest climbs, creating a gap, then riding steadily to the line. That’s where I was lacking.

Then there’s the superstition about spilling salt. One night midway through the Tour of Italy, my CSC teammate Michael Sandstød decided to risk breaking the rule. He purposely knocked over the salt shaker, then poured out the salt in his hand and tossed it all around, laughing, saying, “It’s just salt!” We laughed too, but more nervously. The next day, Michael crashed on a steep downhill, breaking eight ribs, fracturing his shoulder, and puncturing a lung; he nearly died. After that, I started carrying a lucky vial of salt in my jersey pocket, just in case.

As it turned out, I almost won the Tour of Italy. But on the last mountain stage, with three kilometers to go in the final climb, I ran out of energy—bonked, hit the wall. I ended up finishing second to the Italian known as “the Falcon,” Paolo Savoldelli. I made a classic mistake: I felt so good and so strong that I forgot to eat enough. Cecco later informed me that I was probably one 100-calorie energy gel away from winning the race. It was a good lesson, proof of the nature of our sport. You plan for months, you risk jail and scandal, you work harder than you’ve ever worked in your life, and in the end you lose because you didn’t eat a gel.

Even the simplest pleasures became complicated. Girona was a city built for walking, and Haven loved doing the daily rounds to the bakery, the market, the coffee shop. She would ask me to come, but I was always too slow. I know it sounds crazy—I was probably one of the fittest guys on the planet—but I walked like an old man: slowly, with little steps. Naturally, Haven found this irritating, and we’d sometimes get into fights about it.

After getting my early BB, I was concerned about getting tested—and sure enough, the next morning, our team was chosen to be tested. Fortunately for me, the protocols worked in my favor: as is customary, the riders were given a brief window of time after being notified to produce themselves to be tested. It’s not a lot of time, but it’s enough to get an intravenous bag of saline we called a speed bag which lowered the hematocrit by about three points. This is where the soigneurs and team doctors really earn their money: they’re constantly on standby, in case they’re needed. CSC’s crew was as good as Postal’s. One speed bag later, I was back in the safe zone. It’s a team sport.

A little math: the leader on a climb typically spends 15 to 20 more watts than the guy in his slipstream. That’s why you want to follow as much as you can, conserving your energy for the key moments, the attacks and replies. The phrase we use is “burning matches,” meaning that each rider has a certain number of big efforts he can make.

I shared my concerns that our phones had been hacked with my dad, who did his part by ending our telephone conversations with “ … and by the way, fuck you, Lance.”

I'm James—an engineer based in New Zealand—and I have a crippling addiction to new ideas. If you're an enabler, send me a book recommendation through one of the channels below.