The author experienced the WWII bombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, hiding in a bunker underneath a slaughterhouse. It took him 23 years to figure out how to describe what he went through during the war, and in the years following, and he decided on a novel (presumably) so that he could distance himself from the events via the protagonist, Billy Pilgrim. A haunting depiction of what severe PTSD is like, with some pretty good dark humour thrown in.

I have this disease late at night sometimes, involving alcohol and the telephone. I get drunk, and I drive my wife away with a breath like mustard gas and roses. And then, speaking gravely and elegantly into the telephone, I ask the telephone operators to connect me with this friend or that one, from whom I have not heard in years.

On the eighth day, the forty-year-old hobo said to Billy, “This ain’t bad. I can be comfortable anywhere.” “You can?” said Billy. On the ninth day, the hobo died. So it goes. His last words were, “You think this is bad? This ain’t bad.”

Billy coughed when the door was opened, and when he coughed he shit thin gruel. This was in accordance with the Third Law of Motion according to Sir Isaac Newton.

Billy Pilgrim says that the Universe does not look like a lot of bright little dots to the creatures from Tralfamadore. The creatures can see where each star has been and where it is going, so that the heavens are filled with rarefied, luminous spaghetti.

Under morphine, Billy had a dream of giraffes in a garden. The giraffes were following gravel paths, were pausing to munch sugar pears from treetops. Billy was a giraffe, too. He ate a pear. It was a hard one. It fought back against his grinding teeth. It snapped in juicy protest.

Rosewater said an interesting thing to Billy one time about a book that wasn’t science fiction. He said that everything there was to know about life was in The Brothers Karamazov, by Feodor Dostoevsky. “But that isn’t enough any more,” said Rosewater.

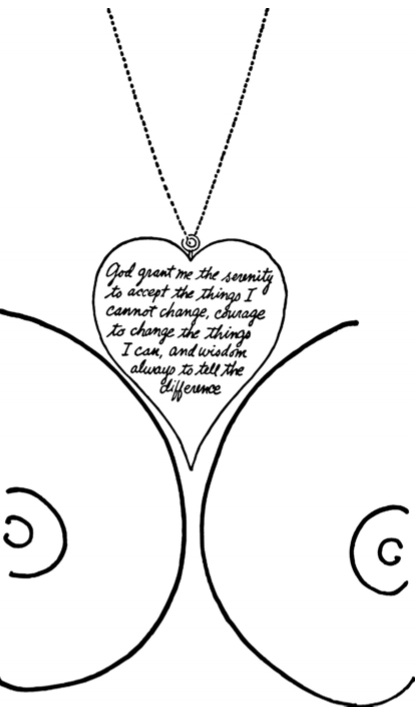

America is the wealthiest nation on Earth, but its people are mainly poor, and poor Americans are urged to hate themselves.

Americans, like human beings everywhere, believe many things that are obviously untrue, the monograph went on. Their most destructive untruth is that it is very easy for any American to make money. They will not acknowledge how in fact hard money is to come by, and, therefore, those who have no money blame and blame and blame themselves. This inward blame has been a treasure for the rich and powerful, who have had to do less for their poor, publicly and privately, than any other ruling class since, say, Napoleonic times.

Trout, incidentally, had written a book about a money tree. It had twenty-dollar bills for leaves. Its flowers were government bonds. Its fruit was diamonds. It attracted human beings who killed each other around the roots and made very good fertilizer.

The advocates of nuclear disarmament seem to believe that, if they could achieve their aim, war would become tolerable and decent. They would do well to read this book and ponder the fate of Dresden, where 135,000 people died as the result of an air attack with conventional weapons. On the night of March 9th, 1945, an air attack on Tokyo by American heavy bombers, using incendiary and high explosive bombs, caused the death of 83,793 people. The atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima killed 71,379 people.

Billy found himself paired as a digger with a Maori, who had been captured at Tobruk. The Maori was chocolate brown. He had whirlpools tattooed on his forehead and his cheeks. Billy and the Maori dug into the inert, unpromising gravel of the moon. The materials were loose, so there were constant little avalanches.

I'm James—an engineer based in New Zealand—and I have a crippling addiction to new ideas. If you're an enabler, send me a book recommendation through one of the channels below.