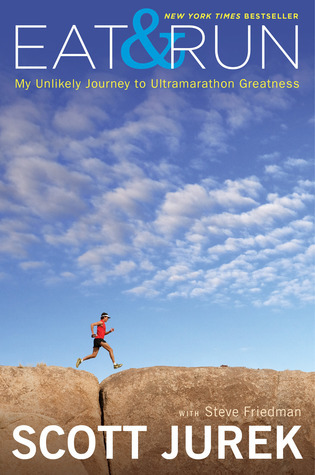

Scott Jurek is a believable writer in the endurance sport space. This book is his account of his two decades at the top of international ultrarunning, and the training and plant-based diet that sustained him. Good yarns throughout and some decent recipes dotted between the chapters. Lots of beans.

Some people needn’t bother with stretching. If you have good biomechanics, don’t spend a lot of time in front of a computer, and have the kind of lifestyle where you can nap or take a dip in the ocean whenever you want, you might be one of them. Otherwise, stretch.

Focus on the “runner’s five”: hamstrings, hip flexors, quadriceps, calves, and the iliotibial (IT) band, or connective tissue that runs from your hip down the outside of the leg. These are the muscle groups that tighten even when people aren’t running, from bad posture, sitting, repetitive activities, and just living.

Though there are myriad exercises to choose from for each area (I suggest The Whartons’ Stretch Book for clear instructions and diagrams), what’s important is to do them correctly and regularly.

This exercise uses the Active Isolated Stretching (AIS) technique, which I prefer and which is quick (you can do your daily routine in 5 to 10 minutes), easy, and effective. Whether you stretch before exercise or after (as I do), using the active isolated technique, there’s no excuse not to stretch.

Bushido is letting go of the past and the future and focusing on the moment. As Thoreau, an American practitioner (though he probably didn’t realize it) of bushido and a pretty good distance walker himself, wrote, “Our life is frittered away by detail. An honest man has hardly need to count more than his ten fingers … simplicity, simplicity, simplicity.”

Making sure you take in enough water and salt during a long period of intense effort sounds simple. Tell that to your stomach. A race is a “fight or flight” situation, so my sympathetic nervous system was fired up, shunting blood away from my digestive organs and toward the muscles, lungs, heart, and brain. The pounding of my feet against the ground raised the pressure in my abdomen to two to three times its normal level. Under those conditions, it’s hard to keep anything down.

There are a lot of ways to live frugally. I know that better than anyone. But the fuel and medicine—the food—I put in my body was not the place to scrimp. My never-better vigor and well-being made the extra investment a no-brainer.

In a sprint, if you don’t have perfect form, you’re doomed. The ultra distance forgives injury, fatigue, bad form, and illness. A bear with determination will defeat a dreamy gazelle every time. I can’t count the number of times people have said, “I can’t believe he beat me.” Distance strips you bare.

I remembered the tribe. The Tarahumara were the middle-aged guys in togas who smoked cigarettes before the Angeles Crest 100 and couldn’t run downhill.

The sun was up, and we were sweating profusely. Caballo suggested we wait, that maybe the Tarahumara would join us here. He warned us that they were incredibly shy, that we should not be too loud or aggressive if they showed up. We shouldn’t try to shake their hands. Their greeting consisted of lightly touching fingertips, nothing more. He also mentioned that it would be good etiquette to bring gifts. He suggested Coca-Cola and Fanta sodas. I was appalled. I hadn’t traveled the length of a country in order to bestow on an indigenous group of athletes plastic containers filled with high-fructose corn syrup. Why not just bring some blankets infested with smallpox? But Caballo insisted.

People asked me later if I had let him triumph in the interest of cross-cultural understanding or as a gesture of kindness. Those people didn’t know how important competing was to me. Arnulfo beat me fair and square. But I returned the next year and got him by 18 minutes. I gave the corn and the $750 to the Raramuri.

Conventional wisdom holds that our ability to push ourselves and keep pushing is limited by peripheral measures of fitness such as VO2 max, the amount of oxygen we can use for aerobic respiration, and lactate threshold, the point at which our muscles accumulate lactic acid faster than they can clear it. Efficiency comes into play in determining how well we can exploit our body’s fitness level, as does the resilience of our muscles and bones. In an ultra, there are the additional issues of maintaining hydration and nutrition.

The most famous long-distance race with a Greek origin is the marathon, which celebrates the arduous journey of the messenger who ran from Marathon to Athens, a distance of 26.2 miles, to announce Greece’s victory over the Persians in 490 b.c.; he then dropped dead from exhaustion. Though Pheidippides is the messenger most often credited with the noble and fatal trip, the runner was probably named Eucles, according to the ancient writer Plutarch.

The reward of running—of anything—lies within us. As I sought bigger rewards and more victories in my sport, it was a lesson I learned over and over again. We focus on something external to motivate us, but we need to remember that it’s the process of reaching for that prize—not the prize itself—that can bring us peace and joy.

I didn’t notice my broken toe anymore. The rest of my body ached, but I didn’t care. That’s one of the many great pleasures of an ultra-marathon. You can hurt more than you ever thought possible, then continue until you discover that hurting isn’t that big a deal. Forget a second wind. In an ultra you can get a third, a fourth, a fifth even.

When I passed Korylo, he seemed to barely be moving. I ran as hard as I could. “Good job,” I said, and tried to run even harder. I couldn’t keep this pace up for long, but I knew how demoralizing it was to be passed by someone moving at a pace you knew you couldn’t match. I was sympathetic to him and admired his courage and tenacity, but when you have a chance to demoralize a competitor, you take it. I took it.

I'm James—an engineer based in New Zealand—and I have a crippling addiction to new ideas. If you're an enabler, send me a book recommendation through one of the channels below.